For any brand, the end goal of community building is to make an impact. Everything a brand does to build a community should ultimately focus on customer retention, which indirectly leads to sales. Some brands in the Chinese market have successfully monetized their communities by incentivizing community members to play an active role in the sales and marketing process. In this article, we’ll explore how community monetization works in practice.

In this article you’ll learn…

Group buying monetization

The rise of e-commerce and social selling in the Chinese market has unleashed an entrepreneurial boom, unlike anything seen in any other developed economy. Anyone can set up an online store, live-stream, or social commerce channel, and—in theory, everyone can build a large enough following to secure brand cooperations and make a living as a KOL. More Chinese people than ever are deriving their income directly from the sale of goods, even if they don’t think of themselves as salespeople.

This surging sales economy is reshaping the Chinese market, with multi-level marketing models becoming ever more prominent. The explosive growth of Pinduoduo is a case in point. In November 2019, the company surpassed Baidu’s market capitalization making Pinduoduo the country’s sixth-largest Internet company just behind giants like Alibaba, Tencent, Meituan, and JD.com.

The people who have made Pinduoduo’s monetization model so successfully don’t even necessarily make money from their “sales” work. The company relies on a non-salaried workforce who make sales by rallying their networks to sign up for heavily discounted products and services. This army of volunteers is willing to trade their time and influence in return for a share of those discounts, although group-buying ringleaders do receive a financial reward for their efforts.

As passive consumers become active participants in the sales process, there are wide-ranging repercussions for the way commerce is conducted in China. Engagement is replacing ownership as the vital force of motivating consumption. And just as this unprecedented army of consumers has grown comfortable with their new roles as salespeople for brands, they are also knocking at the door and demanding a role in other processes.

Social commerce is at the nexus of everything brands do within the Chinese market, from research and innovation to marketing and communications. Brands should embrace this paradigm shift and tap into their most influential consumers’ creative energy, allowing them to play a constructive and organic role in directing the brand toward the future.

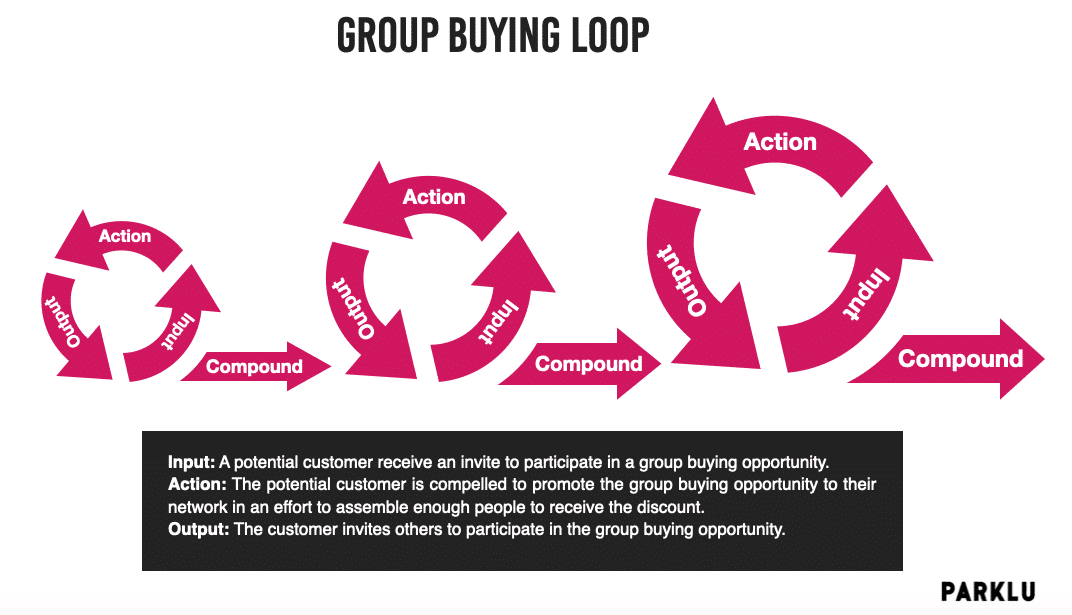

The group-buying business model utilizes principles of multi-level marketing. The individual buyer can access a given brand’s products and services at a heavily discounted rate. The brand enters into this bargain on the condition that a minimum quota of customers will sign up to purchase at an agreed time. This is the input phase of the loop, followed by the “action” phase, where customers who are interested in the deal promote the discount within their circle of friends and followers. As these consumers exert their influence on their networks, more and more buyers sign up. When the threshold is crossed, the discount is triggered, and the transaction between brand and group is completed.

The output of each transaction—and the source of group-buying’s compounding power—is a cumulatively larger squad of group-buying enthusiasts keen to recruit fellow consumers to score these bargains. With each cycle that passes, these group-buying KOC sharpen their powers of persuasion, refining their tactics and sales pitch. They’re also continually evaluating their network, developing a keen sense of who their own “consumer” is as they gain a deeper understanding of who in their circle might be an appropriate target market for a given product or service.

Chinese law prohibits businesses from using multi-level marketing to create pyramid schemes. Multi-level marketing networks are only allowed to operate two layers deep, so companies must be careful with how they structure their operations. For example, one seller can receive compensation or rewards for any purchases or signups sourced from their immediate networks. That seller’s contacts can then tap into their network, but the original seller will receive no rewards for the ensuing sales or signups.

Companies in the Chinese market are pushing the boundaries to explore what rewards a multi-level marketing strategy can bring. And they’re finding out that the potential extends far beyond filling seats in movie theaters or helping restaurants push a few extra desserts. In late 2018, Pinduoduo launched an ambitious program called the “New Brand Initiative.” The platform recognized that by acting as an interface between partner brands and its army of consumer salespeople, it could help transform companies from part suppliers into genuine brands with their line of products. The goal of the audacious plan is to leverage its community’s power to catalyze the development of 1,000 “Original Brand Manufacturers."

The New Brand Initiative mainly recruits Pinduoduo’s non-salaried “workforce” of group buying enthusiasts to serve three functions: focus group, sales team, and the end consumer. Pinduoduo shares big data consumer analytics with partner companies, feeding the companies’ research teams, and helping them develop products that meet needs cited by Pinduoduo group-buyers. As these products are designed, they are put up for sale, discounted of course, via the Pinduoduo platform. The Pinduoduo sales forces will naturally be enthusiastic champions of the products—after all; they were designed literally for those same people. Group-buyers will rally around the products, and the brands walk away with a sales success and—more importantly—a breakthrough, reputation-making hit product.

Jiaweishi was one of the program’s first triumphs. The company had been a supplier for brands including Honeywell, Whirlpool, and Philips. With Pinduoduo’s assistance, it developed its robot vacuum, racking up RMB 30 million sales via the platform in the first year. Pinduoduo accounted for 60 percent of Jiaweishi’s total domestic sales for the year.

Subscription monetization

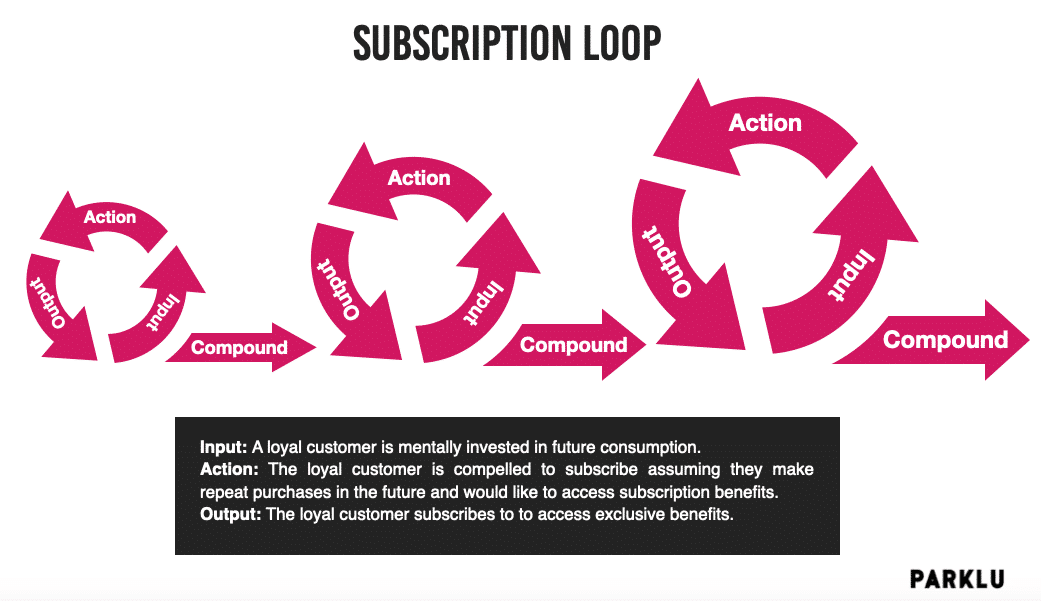

Subscription-based businesses are another specific form of monetization of a brand community. It’s perhaps the oldest such model, dating back to 17th-century publishers. In this model, membership of the community necessitates a purchase, so the consumer is inseparable from the community. For some brands, the product itself will be sufficient to entice consumers to make the purchase. However, the brand can always flesh the membership package out with special offers and features to make it more compelling. Although a brand will limit its potential market by requiring the commitment of a subscription upfront, the model’s logic is sound. Subscriptions are likely to appeal to the kind of consumers who value the sense of belonging a good community provides, and who are likely to make repeat purchases.

Case Study: MollyBox Subscriptions

After an unsuccessful first wave of subscription-based startups went up in smoke around 2013, the concept looked dead and buried. Some thought the subscription model was ill-suited to the Chinese market, but now consumers have fully embraced subscriptions and membership-based commerce in general. In China, the first Costco store was so eagerly received that overcrowding forced the store to close early on its opening day in August 2019.

Subscription-based cat supplies brand MollyBox is one of the outstanding success stories of the genre. Around 70 percent of the company’s revenue comes from subscriptions, with an estimated 200,000 cat owners signed up in 2019. One reason for the brand’s success is that it puts a great deal of control in the subscriber’s hands. Members can choose their cat’s favorite flavors of food, which MollyBox then supplements with a range of snacks, toys, and other kitty essentials. The company also offers a robust e-commerce store for one-off purchases, catering to every feline whim.

Another smart monetization feature of the brand’s success is that it engages its literal consumers for social marketing campaigns. The company runs an MCN promoting KOL pets, which operates out of a fully equipped production studio at the MollyBox headquarters.

Case Study: Yunji

The self-described “social e-commerce platform” offers discounts and benefits to its membership-based network. Yunji partners with global brands like L’Oreal and Procter & Gamble, but it’s also open to working with relatively unknown local manufacturers. The monetization model is that: users pay a fee to sign up, unlocking access to the platform’s special offers. Members can also open a store, “stock” it with products discounted on the platform, and sell to their network outside Yunji. The idea is to leverage the inner circle of Yunji customers—the members—to reach the outer circle—their contacts. Members receive rewards for successfully making sales or recruiting new members.

Initially, the platform was rewarding sellers with physical prizes and cash incentives. However, in 2017, Yunji was fined after falling foul of the Chinese government’s anti-pyramid scheme regulations. Chastened by that experience, the company ceased that practice. Instead, Yunji now awards its sellers with a virtual currency that can only be used to make purchases. This approach is now viewed as a best practice in the field.